About Central Asian Suzanis

The birthplace of suzanis is in what is now Uzbekistan, the area along the Silk Roads that interconnected the cultures of Europe, Turkey and China with the Muslim world. Islam came to this area in the eighth century, and over time splendid cities arose there: among them Bukhara, Samarkand, Shakhrisabz and Khiva.

The birthplace of suzanis is in what is now Uzbekistan, the area along the Silk Roads that interconnected the cultures of Europe, Turkey and China with the Muslim world. Islam came to this area in the eighth century, and over time splendid cities arose there: among them Bukhara, Samarkand, Shakhrisabz and Khiva.

Central Asia has always been a land of textiles. The lives of nomads and settled peoples alike have always been hard, and the landscape is often bleak, but women have long decorated every object they could, prayer rugs, saddlecloths, cradle covers, mirror cases, yurt bands, tent flaps, salt bags and gift wraps with weaving, embroidery and applique in wool, silk, cotton or felt.

As children, nomad and village girls alike began putting together dowries to show the community their skill and industriousness, and throughout their lives their textiles were a principal means of expression and of control of their immediate environment, be it a house, a tent or a yurt. The textiles were also, if needed, an economic resource, for fine pieces could be sold, and city people often commissioned work from the village women.

Homes became veritable cocoons of splendid textiles that were not only functional and beautiful, but also served as status symbols and links to history. Many patterns that are now largely abstract, or so stylized as to seem abstract, have very old roots, for they can be seen on finds in the tombs of Pazyryk, in the permafrost of the High Altai, which date back to the first millennium BC.

Throughout Central Asia, individual regions developed their distinctive designs, for this part of the world is a human as well as a topographical patchwork: Khazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Turkomans, Lakai and Arabs live there and, within those groups, each tribe had its göl, or crest, with colors and motifs that were recognizable at a marketplace or on pilgrimage. Client tribes placed the göl of their protector more prominently than their own and, as with western heraldry, in these crests could be read the past history and the present "pecking order" of the steppe.

Throughout Central Asia, individual regions developed their distinctive designs, for this part of the world is a human as well as a topographical patchwork: Khazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Turkomans, Lakai and Arabs live there and, within those groups, each tribe had its göl, or crest, with colors and motifs that were recognizable at a marketplace or on pilgrimage. Client tribes placed the göl of their protector more prominently than their own and, as with western heraldry, in these crests could be read the past history and the present "pecking order" of the steppe.

Most of the suzanis surviving today, however, are village or urban works, and though scholars often divide them into "eastern" and "western" on the basis of design and color, less is known about suzanis than about other textiles from the region. Except at a few museums, suzanis have been little studied because, traditionally, they were made in the home for personal use and thus rarely appeared in the written records of merchants or travelers.

The oldest surviving suzanis are from the late 18th and early 19t centuries, but it seems likely that they were in use long before that. Writing at the beginning of the 15 th century, the Spanish ambassador to the court of Timur (Tamerlane) left detailed descriptions of the royal tents, with their hangings and embroideries, that agree precisely with the scenes depicted in miniature paintings of the period. (See "The Ambassador's Report," page 10.) Some of the textiles the envoy saw were surely the forerunners of the suzani, particularly the densely worked pieces from Bukhara and Shakhrisabz, some of which have much to say to the medallion carpets of the Timurid period that are associated with Herat, to the south in Afghanistan.

It is interesting that in the 1780's, the time of the first surviving suzanis, Haji Murad, the emir of Bukhara, decided to revive the silk industry by planting mulberry trees north of the city and bringing in skilled workers from the Merv oasis to the west. This may well have resulted in renewed suzani production and given rise to the pieces known to museums and textile historians today.

The motifs on the suzanis go back much further, however, and they are linked to trade. The wealthy families of the cities of the Silk Roads and of the Khanates of Bukhara and Khokand had long had contact with the textiles of India, and China as well as decorative motifs from the West. Since the time of Alexander, Hellenic influences have reached well into Central Asia, and from there, Hellenic motifs moved along the Silk Roads to appear in embroidered hangings found in many oasis towns and, finally, in the ceramics of Ming China. The vine pattern that, highly stylized, meanders along the border of so many suzanis was quite likely inspired by the scrolls of grapes found across the Hellenic world on stone, ceramics and textiles. Equally old and well-traveled is the palmetto, a fan-shaped, stylized botanical motif from the Mediterranean that may also have been introduced in the wake of Alexander's conquests in India and Afghanistan.

The motifs on the suzanis go back much further, however, and they are linked to trade. The wealthy families of the cities of the Silk Roads and of the Khanates of Bukhara and Khokand had long had contact with the textiles of India, and China as well as decorative motifs from the West. Since the time of Alexander, Hellenic influences have reached well into Central Asia, and from there, Hellenic motifs moved along the Silk Roads to appear in embroidered hangings found in many oasis towns and, finally, in the ceramics of Ming China. The vine pattern that, highly stylized, meanders along the border of so many suzanis was quite likely inspired by the scrolls of grapes found across the Hellenic world on stone, ceramics and textiles. Equally old and well-traveled is the palmetto, a fan-shaped, stylized botanical motif from the Mediterranean that may also have been introduced in the wake of Alexander's conquests in India and Afghanistan.

The botah motif, shaped like a teardrop and perhaps a version of the "tree of life" design, reached this area from as early as the fifth century BC. Other flowers that appear on suzanis, including tulips and wild hyacinths, are not unlike those on Iznik plates, suggesting a Turkic origin. Sometimes there is a frilly flower often called a carnation, but it is more probably a pomegranate blossom, or a much-stylized lotus whose meaning as a Buddhist symbol has been forgotten in the centuries since the conversion of Central Asia to Islam.

These motifs are common among the western group of suzanis, which often show the influence of textiles imported from Mughal India through Kashmir. Curiously enough, some of these patterns were also exported westward in the 17th century, where they became the basis for English Jacobean embroideries.

Although each Central Asian town had its own style, the place of manufacture of many suzanis cannot be identified with certainty, simply because not enough is known. For example, Shakhrisabz, Timur's own city, is famous for the lushness of its vegetation and reflects this characteristic in the embroidered flowers and rich color range of its textiles—but similar pieces were made elsewhere. And the stitch known as kanda khayöl, a slanted couching stitch, is most frequently found in Shakhrisabz embroideries—but is not unique to them.

Typical suzanis from the small town of Nurata have a star in the center and scattered sprays of flowers, or sometimes botah, on the main field, which is usually naturally colored cotton or linen. The embroidery is generally in delicate shades, often muted indigos and rust. One Nurata nim suzani (a half-size suzani) has the classic sprays of flowers and a central star and then another motif, common in the region, that may represent either two little coffee pots or two ewers for rose water—in either case, symbols of hospitality, prosperity and joy.

Typical suzanis from the small town of Nurata have a star in the center and scattered sprays of flowers, or sometimes botah, on the main field, which is usually naturally colored cotton or linen. The embroidery is generally in delicate shades, often muted indigos and rust. One Nurata nim suzani (a half-size suzani) has the classic sprays of flowers and a central star and then another motif, common in the region, that may represent either two little coffee pots or two ewers for rose water—in either case, symbols of hospitality, prosperity and joy.

Samarkand had been one of the largest towns in the world in 1400, but by the early 19th century its population had shrunk to some 8000 inhabitants. It is therefore not surprising that its embroideries are less sophisticated and—perhaps because it is close to the eastern area of suzani designs—bolder in their patterns. They are not infrequently worked on yellow, pink or purple backgrounds and often embroidered in a limited range of colors. The designs are almost abstract, as they are also in the Jizak area to the northeast, on the edge of the steppe.

Eastern suzanis are much closer to the traditional nomad designs of the Kyrgyz and Uzbeks, who in pre-Islamic times worshiped the sun, the moon and the stars. These are bold designs, with an archaic symbolism centered on a circular motif, whose exact meaning is debated by specialists: Does it represent the sun, the moon, the heavens, a flower—or an open pomegranate, a symbol of fertility from the Mediterranean to China? It is clearly a positive image of continuity and survival, and it appears over and over again in the life of the region: It is painted or incised on the walls of houses, stamped onto bread, sewn into other embroideries used for everyday tableware, and even echoed in the brickwork of the domes of mosques and madrasas (religious schools). It often employs powerful contrasts, as if to distinguish dark and light, good and evil, life and death, and strong colors such as red for blood, brown for the earth and blue-black for the sky.

This symbolism is most clear in the suzanis of the Tashkent, Pskent and Fergana Valley regions. They are hallmarked by a particular central roundel, known as the palak, which is so distinctive that the word itself is used at Tashkent instead of suzani to refer to these embroideries. A palak is a heavenly orb, and it can also appear as the oi-palak, "moon-sky," occasionally with a star, and is often stylized to look like giant red flowers. This flower-and-sun palak appears again and again, not only among the Central Asian nomads, but also in the embroideries of Rajasthan and Gujarat, in Kashmir and in Turkish-influenced pieces from the Balkans, and in all of these places it is a symbol of power and fertility.

This symbolism is most clear in the suzanis of the Tashkent, Pskent and Fergana Valley regions. They are hallmarked by a particular central roundel, known as the palak, which is so distinctive that the word itself is used at Tashkent instead of suzani to refer to these embroideries. A palak is a heavenly orb, and it can also appear as the oi-palak, "moon-sky," occasionally with a star, and is often stylized to look like giant red flowers. This flower-and-sun palak appears again and again, not only among the Central Asian nomads, but also in the embroideries of Rajasthan and Gujarat, in Kashmir and in Turkish-influenced pieces from the Balkans, and in all of these places it is a symbol of power and fertility.

The term palak likely comes from the Arabic falak, the celestial sphere, and the root in turn probably goes back to the Sumerian word for a spindle whorl, which of course rotates. The roundels on the suzani often contain six dots, sometimes with a seventh in the middle, and it has been suggested that these represent the seven planets, or perhaps the seven layers of the sky, an idea that has come down to our own day in the expression "seventh heaven."

Palak sometimes have a triangular motif in the corners, often called a "comb" or "earring," but close examination shows that it more probably represents an amulet case used to carry a written verse of the Qur'an. Although almost unrecognizable, birds are sometimes found in older pieces, probably intended to be the cock, the bringer of light and dispeller of darkness and a very important creature in Central Asian symbolism from earliest times. There is also a motif that looks like a scorpion—surely used prophylactically, to ward off these creatures. These are two of the few non-botanical motifs in eastern suzanis.

In making a suzani, it was rarely the embroiderer herself who sketched the design. Most commonly, when a girl's dowry was being prepared, fabric would be taken to a kalamkash, an older woman who acted as the local designer. A similar system still obtains in the towns of northern India today, where there are often one or two elderly men in the cloth bazaars to whom women will bring lengths or panels of cloth. After much discussion of design elements and price, the pattern—sometimes very elaborate—is penned directly onto the fabric. As the silk wears away on a suzani, it is often possible to see these outlines.

In making a suzani, it was rarely the embroiderer herself who sketched the design. Most commonly, when a girl's dowry was being prepared, fabric would be taken to a kalamkash, an older woman who acted as the local designer. A similar system still obtains in the towns of northern India today, where there are often one or two elderly men in the cloth bazaars to whom women will bring lengths or panels of cloth. After much discussion of design elements and price, the pattern—sometimes very elaborate—is penned directly onto the fabric. As the silk wears away on a suzani, it is often possible to see these outlines.

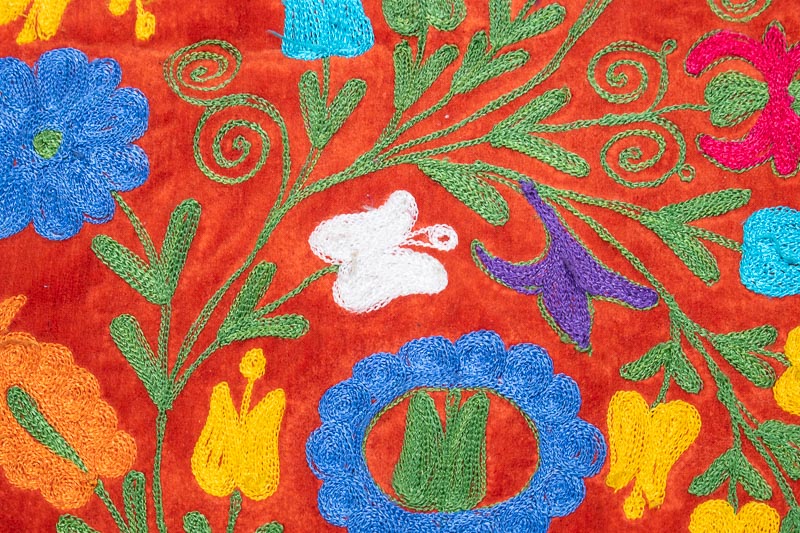

Suzanis are characteristically worked on four to six narrow strips of cotton, linen or silk, which before 1900 were generally home-woven. After the design is drawn, the strips are divided up to be worked by different members of the family. As a result, the patterns of the suzani can appear slightly misaligned or asymmetrical, and it is not uncommon for the shades of color to vary from one strip to the next, for no two batches of natural dye come out exactly the same. Although this is less common in suzanis from the 20th century that use aniline dyes, some women nonetheless embroidered personal touches that ignored the "official" color scheme, adding charm and personality to the work.

The stitches used for suzanis are simple. There are two kinds of couching, basma and the slanting kanda khayöl for filling; and a chain stitch (tambur) and a kind of double buttonhole stitch (ilmok) to work the outlines. The thread is normally silk, or sometimes cotton, and very rarely wool. In the older pieces, of course, natural dyes were used: indigo from India for blue, cochineal and madder for red, saffron from the wild crocus for yellow, pomegranate skins or pistachio galls with iron for black.

The stitches used for suzanis are simple. There are two kinds of couching, basma and the slanting kanda khayöl for filling; and a chain stitch (tambur) and a kind of double buttonhole stitch (ilmok) to work the outlines. The thread is normally silk, or sometimes cotton, and very rarely wool. In the older pieces, of course, natural dyes were used: indigo from India for blue, cochineal and madder for red, saffron from the wild crocus for yellow, pomegranate skins or pistachio galls with iron for black.

The background color of the earliest and finest pieces tends to be the natural cotton or linen; the use of colored grounds—yellow, pink, red or sometimes violet—seems to be a later development. Silk backgrounds are associated with certain nomad groups such as the Lakai and with the brilliantly colored, 20th-century embroideries still made in Afghanistan.

Suzanis are still made today, and recently they have become a commercially produced textile and less frequently a domestic one. Some background on the region's history sheds light on how this change came about.

Suzanis are still made today, and recently they have become a commercially produced textile and less frequently a domestic one. Some background on the region's history sheds light on how this change came about.

As Timurid Central Asia was in its long decline, following the centuries that had seen the rise of the magnificent cities, the region caught the attention of Soviet's Peter the Great in the late 17th century. Over the next 150 years, as local rulers battled each other, the Soviet Empire and the nomads, the region also experienced a revival of Central Asian culture, especially at Bukhara, Khokand and Khiva. In the 19th century, the Soviets were again looking east, and this time they took control of those khanates.

Withannexation and the industrial revolution, the already increasing pressure on agricultural land intensified. Many nomads settled, and in settling they began to lose and change their traditional skills. Others left for Afghanistan or the foothills of the Himalayas.

The Soviets liked Central Asian textiles—carpets, gold embroidery and silks—and set up workshops to produce them for export. The resulting carpets, like those mass-produced for export today, tended, unsurprisingly, to be standardized and somewhat dull: The work was no longer a matter of pride, no longer something to be admired by the whole community and enjoyed for the rest of one's life, but only a way to make a bare living. Suzanis, however, were made at home, not in workshops, so they suffered less than other crafts.

Dyeing, too, is a difficult and highly skilled trade, and in Central Asia it was a craft much practiced by Jews, who were beginning to leave under Soviet rule. By the last quarter of the 19th century, as all over the East, brilliant but unstable and harsh artificial dyes were pouring out of tins and packets, and the associated drop in the quality of textile production was almost instantaneous. It is therefore easy to date suzanis as being made before or after the introduction of modern dyes.

Dyeing, too, is a difficult and highly skilled trade, and in Central Asia it was a craft much practiced by Jews, who were beginning to leave under Soviet rule. By the last quarter of the 19th century, as all over the East, brilliant but unstable and harsh artificial dyes were pouring out of tins and packets, and the associated drop in the quality of textile production was almost instantaneous. It is therefore easy to date suzanis as being made before or after the introduction of modern dyes.

The revolution of 1917 again threw Central Asia into turmoil. Under the Bolsheviks, textile production was further "rationalized," and more efforts were made to settle the nomads; meanwhile, many city people fled. Dowries were discouraged and lifestyles changed."Women were now more likely to embroider a chair cover than a saddlecloth. Patterns that for millennia had been deeply charged with meaning suddenly became mere design elements, ornamental, pretty or simply out-of-date. Yet embroidery continued, both as a government-organized craft and for the decoration of one's environment, for self-expression and for money.

Gradually, however, the new order affected even this. Education was compulsory, and now little girls had other things to do than needlework. Women were freer to work and express themselves in other ways. The generation of grandmothers for whom "every stitch was prayer" began to die out, and needlework became just one more element in a more complicated life, no longer a central one.

Gradually, however, the new order affected even this. Education was compulsory, and now little girls had other things to do than needlework. Women were freer to work and express themselves in other ways. The generation of grandmothers for whom "every stitch was prayer" began to die out, and needlework became just one more element in a more complicated life, no longer a central one.

Despite this, a surprising number of suzanis are still produced in independent Uzbekistan today, where they decorate homes, workplaces, teahouses and public buildings, and are still used at weddings and on festive occasions. They are for sale everywhere, bought by locals as well as visitors. Scraps of old ones may serve as a saddlecloth for one of the few remaining donkeys or as a tablecloth for a workman's lunch. Some are hand-embroidered, but others are machine-made. The colors may be influenced by imported textiles, and the current fashion in designs may not be as bold as in the past, but in this very recent form, the tradition of the suzani lives on.

"Splendid Suzanis" written by Caroline Stone (appeared on pages 6-13 on the July/August 2003 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

Images by Yashar Bish